The Red East

Krasny Vostok, in the east of Karachay-Cherkessia, is a small and utterly inconsequential village. A village with one foot in the 19th century, still partially without gas and electricity; a village we stumbled across by chance in our search for stories. Barely 200 kilometres from Sochi, but a world away. Except perhaps for falling for the name – Krasny Vostok literally means ‘the Red East’ – there is no reason to portray this village. It is a village like so many in Russia, where the population is dwindling; where industry and activity are disappearing; where a handful of people are attempting to prevent the decline; where Moscow’s politics trickle through slowly; where every day is a struggle to keep the village hanging on. Only when you are familiar with this kind of village, we believe, can you get to know this region better. The Caucasus is more than just conflict and refugees, fundamentalist Islam or billion dollar Games. It is first and foremost a beautiful region, home to several million people trying to make the best of life. In Georgia, Abkhazia, Russia and here in Krasny Vostok, in obscure Karachay-Cherkessia.

View on the bridge in Krasny Vostok, Karachay-Cherkessia, 2013.

View on the bridge in Krasny Vostok, Karachay-Cherkessia, 2013.

Fighting for gas

Taisya Makova

Suddenly the whole village was unemployed.

Krasny Vostok (‘the Red East’) is located in a remote corner of a remote corner of Russia. Immediately after the fall of the Soviet Union the shoe factory closed its doors. The factory for electrical equipment, one village away, did not last long either. Suddenly the whole village was unemployed. The population became dependent on the small fields behind the houses and a few domestic cows and chickens.

The impact was enormous, says Taisya Makova (54), who until 2011 was the mayor of the village. According to the public records, 3,340 people are registered in Krasny Vostok, but in reality only around 1,600 people still live here. With two civil servants the mayor governs the small village hall-cum-cultural centre, library and telephone exchange. She is an enthusiastic woman. With a handful of vassals she is trying to breathe new life into the neglected village. She is called constantly by residents, who report a gas shortage or a problem with the plumbing. Russia may be the largest gas producer on earth, but half of this village does not yet have gas. The mayor then calls her odd-job man (and uncle), who drives round the village in an old Lada looking for the defect. Every day begins with a visit to the school. “The gas and electricity have to work there at least,” says Taisya. She slides her papers off the table and walks outside. She wants to show us the state of the village 20 years after the factory closed. We drive past the main school and the almost closed second school, past muddy streets full of potholes. Old women from the cities have squatted the houses in order to harvest crops in the autumn for their own use. Many streets are deserted.

Albert Ghabatov

“Communism or not, we managed to sustain ourselves.”

Countless families have moved to Sochi, just over the mountains, or cities like Moscow or Kislovodsk in search of work. Attached to the houses that are still inhabited is a sizeable plot of land, where set amounts of corn, potatoes, herbs, vegetables and fruit are grown. “It’s actually never been very different,” says Albert Ghabatov, an unemployed builder who lives on one of the deserted streets. “Communism or not, we managed to sustain ourselves.”

Mohamed Kardanov, 2010

Mohamed Kardanov, 2010

Humiliated by history

On our tour of Krasny Vostok we drop in on Mohamed Kardanov, who, born in 1926, is one of the village’s oldest residents. “I feel humiliated,” he says. “Why have people stolen everything? How could this have happened?” The years following the October Revolution were tough. The Soviet Union was on the brink of large-scale agricultural collectivisation. Mohamed was sent into the fields at age 12. The entire Soviet Union faced famine. Collectivisation had failed, with millions of deaths as a result. Mohamed was quickly assigned to the group of tractor drivers. With large combines they visited the 13 kolkhozs in the area to collect the grain.

When war broke out he stayed behind. “I could have fought,” he says, but he was 15 and still too young. All the men from the village served on the front. The land was left to the women. “The fields were so dusty that the women could only endure it for 20 minutes,” he says. “Even so, we broke our backs working. In 1943 and 1944 we were able to send 700 tons of bread to the front.

Mohamed Kardanov

"In 1943 and 1944 we were able to send 700 tons of bread to the front."

“After the war, I carried on working at the kolkhozs. It was a good life. At our peak – I had already become the boss of the sovkhoz by then – we produced 127 tons of corn per year. That was our republic’s record. I was able to buy accordions for my employees.

“In 1988 I retired. Three years later the sovkhoz was bankrupt. I couldn’t believe it. I said we should work 24 hours a day. We have to maintain discipline, keep listening to your bosses. But there was no competition any more. The best work and the highest production no longer existed. All the farms from those days are now ruined. They’re overgrown. We had nine dairy farms and 22,000 sheep. That was enough for 22 tons of milk and 80 tons of meat per year. Everything is ruined. Over the last years, the sovkhoz has been privatised. It’s a shadow of its former self.

“It’s the biggest mistake in our history, because people did it themselves. Everything was peaceful. People worked and slept. If people are unemployed all their energy is wasted. Imagine how much energy was lost across Russia during the 1990s. We endured some terrible things, such as war and collectivisation, but we worked and laughed.”

On the brink of death

Mohamed Kardanov

"Imagine how much energy was lost across Russia during the 1990s."

Krasny Vostok is a village like any other. There are four small shops, a few dozen kilometres away is a large town and around it is forest and brushwood suitable for hunting or seclusion. In the largest school the auditorium is set up for discos and parties. It is equipped with a clapped-out sound system. The director has become permanently embroiled in an argument with the school’s oldest pupils about the best way to use this without the crackling blowing the speakers. Through the serving hatch is the stolovaya, where old women from the village not only prepare rolls and snacks for breakfast but can also keep an eye on the children in the auditorium. The disco is usually on Saturday afternoon, when people from all over the village come to see the new generation’s dance moves.

Children playing near the administration building, Krasny Vostok, 2009.

Children playing near the administration building, Krasny Vostok, 2009.

We cross the pontoon by the bridge and climb the slope to the village hall-cum-cultural centre. In front of it is a small patch of grass. Under the birch trees is a children’s playground. We ask after the cultural centre’s warden, but the playing boys just snigger. We go upstairs, to the three-room village hall, where the mayor is surely at work. She looks up anxiously when we ask who the warden is. Muhamed Shanov, she mutters and reaches for her telephone. She exchanges a knowing look with the man at her desk. The telephone is not answered. We walk outside with the mayor, looking for the key. Shanov appears at the gate. He staggers and leans against the fence. “Go home,” the mayor calls immediately. “Ah, mayor,” Shanov looks at her affectionately and falters. “He arrived this morning, parked his car and then just disappeared,” says the mayor, shaking her head. “And now he reappears, roaring drunk.” Shanov grumbles something to us before the mayor’s stern looks send him on his way. “You should see the cultural centre tomorrow,” says the mayor. “There’ll be a concert then, too.”

We say goodbye and walk on through the village, in search of entertainment. There must be a local boozer, a café or something; a forlorn wood full of drinks bottles at least. At the river four Ladas are parked higgledy-piggledy in the water. Six young men hang around them, washing them with river water and drinking beer from gallon bottles. Tinny turbo-folk drifts from a mobile phone. All are around 19 years old. They have already served in the army, they tell us proudly. Now, most of them study or work in one of the nearby cities, such as Cherkessk or Kislovodsk.

“There aren’t any plans in Krasny Vostok.”

When we ask what their plans are for that evening, they say, “There aren’t any plans in Krasny Vostok.”

The next day, after having survived a completely ad hoc evening of carousing, we arrive on unsteady legs at the cultural centre to see how the preparations for the concert are coming along. The whole village seems to be looking forward to it. Muhamed Shanov is sitting on a bench. He is also still suffering from the effects of the alcoholic relapse of the day before. “Sorry for yesterday,” he apologies. “It used to be worse.” Since the war in Abkhazia in 1993, he still often dreams of the scenes he witnessed in the hospital there; of stories he heard of Georgians who drank the blood of Abkhazian women, in a glass with salt and pepper. He saw children without hands and feet. Since then he hasn’t been able to keep away from the drink. He had been sober for several weeks, but after the nightmare of two days ago…

That evening, half of Krasny Vostok puts on its best clothes and sets off for the cultural centre. Shanov is nowhere to be found. ‘Cancelled’ has been scribbled on the posters in front of the building. The news spreads slowly. As calmly as everyone arrived, they turn around and leave. In this village where nobody makes plans, few people are surprised when at the eleventh hour the artist fails to show up.

Mayor Taisya Makova. Krasny Vostok, Karachay-Cherkessia, 2010.

Mayor Taisya Makova. Krasny Vostok, Karachay-Cherkessia, 2010.

Hope for the future

Somewhere on the horizon is a glimmer of hope for Krasny Vostok, says the mayor on our first visit in 2010. The 700-hectare state farm, for example, which after having stood empty for nearly 20 years has been bought by a businessman who was born in the village. He made a fortune in Moscow in the turbulent 1990s and this is his way of giving something back. The labourers receive a minimum wage and a percentage of the profit.

Like cowboys they ride on horseback over the rolling hills, the outliers of the mighty Caucasus in the distance.

Like cowboys they ride on horseback over the rolling hills, the outliers of the mighty Caucasus in the distance. In the late afternoon an enormous procession of cows returns to the village. Most of them go to the farm’s barn, while some turn left or right in search of their own individual stalls. And perhaps the old shoe factory in the village will soon be replaced by a mineral water bottling plant.

But, say others, all of Taisya’s predecessors promised to restore the gas and water mains. Some see in the entrepreneur’s offer a way to take their land from them – and that can never be allowed to happen! The local water was once transported to the spas in Kislovodsk, but they now seem to have a sufficient supply.

The local imam, Mohamet Adzhibekov, Krasny Vostok, Karachay-Cherkessia, 2013.

The local imam, Mohamet Adzhibekov, Krasny Vostok, Karachay-Cherkessia, 2013.

The upper mosque of Krasny Vostok, Karachay Cherkessia, 2013.

The upper mosque of Krasny Vostok, Karachay Cherkessia, 2013.

The mores of the mountains

Imam Mohamet Adzhibekov is in charge of the mosque. He meets us in a casual pair of jeans and shirt. He comes from a long line of imams. He himself was educated in Cairo, Egypt and Trabzon, Turkey. He doesn’t attract many worshippers, he tells us. “Every Friday around 30-35 people attend the Friday prayer. Most of them have religious questions. After 70 years of the Soviet Union, no one knows any more what the real Islamic practices are. So people come to me and ask whether they can throw fruit and drinks into the grave at a funeral. It’s not necessary, I say, but neither is there much against it.” The mufti of Cherkessia was recently murdered, on the street, in cold blood. “It might have been the Wahhabis from the neighbouring republics,” says Mohamet. “I don’t know. I try to practise my religion as purely as possible, perhaps that’s why I haven’t had any problems yet.” Girls and women don’t come to his mosque. “Maybe they’re frightened of stories about shari’a. I don’t know.”

After 70 years of the Soviet Union, Krasny Vostok’s inhabitants have little interest in Islam.

It is more likely that after 70 years of the Soviet Union, Krasny Vostok’s inhabitants have little interest in Islam. At home, a hospitable Soviet culture prevails, fuelled by pickles and hefty amounts of vodka and home-made wine. In public, the mores of the mountains hold sway. The mayor is happy to list them for us. “If you cross the street, no one will cross your path,” she begins. “That brings bad luck; we wouldn't do that to each other. Young people must never interrupt old people, even if the old people are wrong. A man on horseback must never pass a woman without first dismounting. Younger sisters may not get married before their older sisters. We don't cover our faces any more, but we don't expose ourselves either. And,” she adds jokingly, “in the Caucasus we don't get drunk. But that’s because of the fresh air.”

The Making of Shashlik. From sheep to toast.

The Caucasus is rife with myths, legends and traditions that are partially mixed with Islam or have nothing to do with it at all. Every mountain has a story, for example. In Dombai, Karachay-Cherkessia’s ski resort, is a mountain that looks like a sleeping woman. Or, as they say here in Krasny Vostok

Krasny Vostok

Karachay-Cherkessia

, the mountain is a sleeping woman. She protects the neighbouring valley from bad weather and disaster. “I can't imagine how people here become fundamentalist,” says someone at our table one evening. Even though we are in Krasny Vostok she wants to remain anonymous. Islam and fundamentalism and the accompanying violence have the fullest attention of all the local security forces. “But with so much unemployment, so few prospects and occasional government strong-arming, the Wahhabis’ message can be very appealing.”

Krasny Vostok

Karachay-Cherkessia

, the mountain is a sleeping woman. She protects the neighbouring valley from bad weather and disaster. “I can't imagine how people here become fundamentalist,” says someone at our table one evening. Even though we are in Krasny Vostok she wants to remain anonymous. Islam and fundamentalism and the accompanying violence have the fullest attention of all the local security forces. “But with so much unemployment, so few prospects and occasional government strong-arming, the Wahhabis’ message can be very appealing.”

During our time in Krasny Vostok we have been staying with the Ekzekov family, where we enjoy the local hospitality and good food. And because in the Caucasus a guest is a gift from God, a sheep is slaughtered in our honour. A friend of the family is great-uncle Husey Aibasov, an inquisitive former policeman, who turns up to drink vodka with his foreign guests whenever he has not ordered a girl on the recently discovered internet. Aibasov’s son is an imam in a village a short distance away. The imam doesn't drink. Aibasov is a former policeman. Not drinking doesn't exist. One Friday we are once again sitting around the table. Our hostess warns us: Aibasov will be here soon and he has had to spend the whole day with his son. He'll be thirsty. And indeed, when Aibasov arrives, he immediately opens a beer with his pistol and knocks back a glass of vodka. When we ask him about his son, he raises his hand. “No questions please. After the third toast,” and quickly knocks back two more. “If you drink, God doesn't hear your prayers for 40 days,” he says then. “But I'll let my son write a letter. Imams have the power to write magical texts, which move people to do things. Unfortunately, for the time being my son doesn't want to abuse that power.”

Preparing for the afterlife

Taisya Makova

Little else has changed in the village. The water and gas still do not work.

Less than two years later, a small revolution seems to have taken place in the village. The mayor has resigned and “a clique around the imam”, as she puts it, has taken the reins. Little else has changed. The water and gas still do not work. The sovkhoz has been abandoned again and the factory is not yet operational. Taisya is scared. “There’s a strong Islamic lobby. As soon as they feel a bite, they reel in the new converts. They won’t stop until we’re all leading Islamic lives.”

The lower mosque, at the riverside in the village. Krasny Vostok, Karachay-Cherkessia, 2013.

The lower mosque, at the riverside in the village. Krasny Vostok, Karachay-Cherkessia, 2013.

In the upper mosque, imam Mohamet Adzhibekov is enjoying grilled chicken dripping with fat. It is shortly after Friday prayers. There were few worshippers that day, perhaps 18 or so of the village’s 1,300 inhabitants. It does not seem like an impressive figure, but the imam is elated. “Everything is changing for the better. More people are coming to the mosque than before. We’re gaining influence in the village, and finally making it clear that those old traditions, such as drinking alcohol or taking drugs, are incompatible with Islam.

“Politics isn’t for me,” continues the imam and recently elected village head. “We’re not too concerned about life now. The afterlife, that’s what it’s all about. That’s what we’re trying to prepare people for. Although I’ve been elected, there’s little room to manoeuvre. We’ll never be able to introduce Islamic laws. We can make rules, as long as they don’t conflict with national laws. We can ensure that people who pray too little or drink too much are no longer greeted on the street, are ostracised. But we can’t prohibit the sale of alcohol.”

Mohamet Adzhibekov

"The crooks are afraid of him. All the corruption you find in Russia is impossible under him.”

The imam’s greatest example is the Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov. “He’s succeeded in implementing the Islamic model within the confines of Russian law. The crooks are afraid of him. All the corruption you find in Russia is impossible under him.”Mohamet believes that an Islamic village and country will be a reality one day. But there is a lot to be done. “We’re still looking for an inspiring leader for our girls. They are already Muslim but they don’t come to the mosque. We need time. You can’t eradicate all those old Caucasian traditions overnight. It will take at least a generation.”

The Red East turns green

“Faith,” says Taisya Makova, the former mayor, “is something personal, something you keep to yourself. Those modern Muslims like to show off. We had to fight to prevent them from building a third large mosque, sponsored by Arabs, next to the school.

Taisya Makova

"The imam was educated at a special place where they ‘breed’ bearded men.”

The imam in the village was educated in Cairo,” she adds ominously, “at a special place where they ‘breed’ bearded men.”

Taisya associates political Islam with suppression and violence, and that violence is creeping closer. The neighbouring republic, Kabardino-Balkaria, is regarded as the new hotbed of the North Caucasus. So far Karachay- Cherkessia has remained largely peaceful. The regional capital is Uchkeken, where Taisya moved to work for the school inspectorate after resigning. The former mayor – as emancipated as it is possible to be in the North Caucasus – becomes angry when she talks about the Muslims. “There’s been a counter-terrorism operation in Uchkeken for almost half a year,” she says. “I’ve seen people shot in the street. That never used to happen.

Chapter VII focuses on the impact of the violence in the North Caucasus.

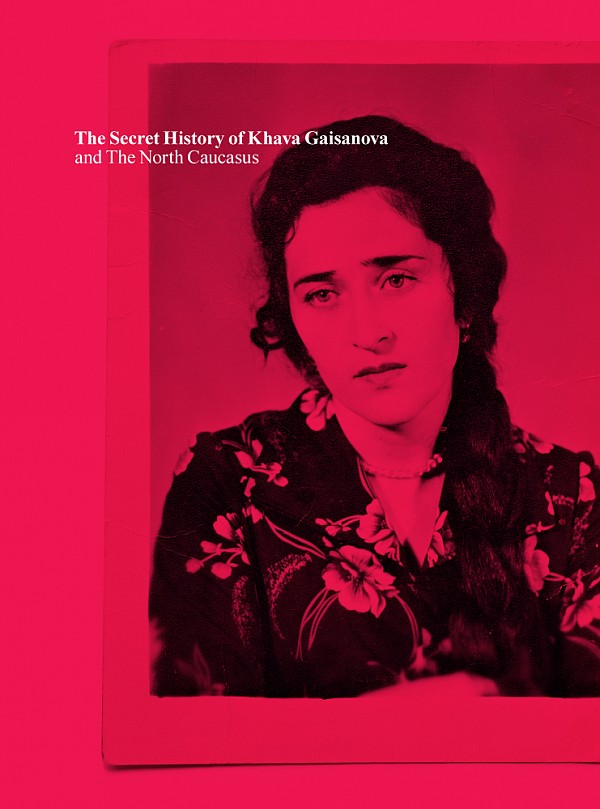

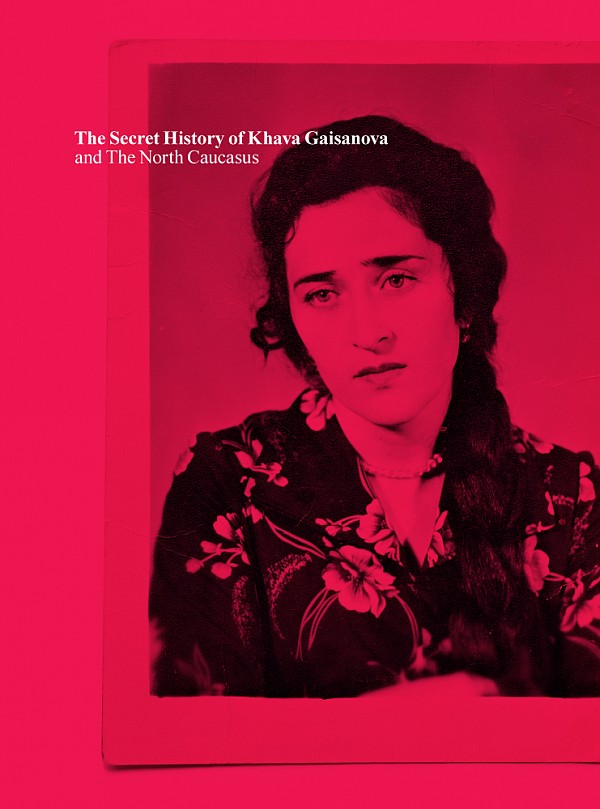

Read more about the North Caucasus, a history of conflict and violence, in The Secret History of Khava Gaisanova on ISSUU. The Secret History of Khava Gaisanova is also for sale in our webshop.

Two of The Sochi Project’s Sketchbooks cover the North Caucasus. Life Here is Serious, about wrestling (issuu + webshoplink) and Safety First, about Chechnya. Chapter IV explains more about the history of the violence.

On the other side of the mountains

On the other side of the mountains

The secret history of Khava Gaisanova / De geheime geschiedenis van Khava Gaisanova

The secret history of Khava Gaisanova / De geheime geschiedenis van Khava Gaisanova

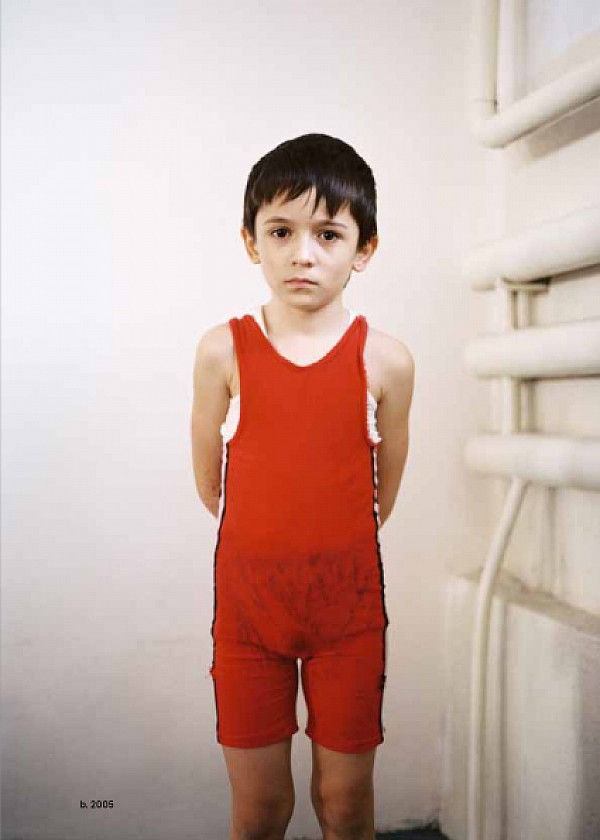

Life Here is Serious

Life Here is Serious

Safety First

Safety First

Share

On the Other side of the Mountains

On the Other side of the Mountains

North-Caucasus

General map

begins promisingly, along the Black Sea coast, where we have to wait 45 minutes at a station for the trains to Moscow to overtake us. The North Caucasians on board stare dreamily out over the sea, for what might be their last time in a long while. One of them even dives off the steep cliff, swims for about a hundred metres and returns to shore, helped up by his comrades and shouted up by the overly anxious train attendant, who feels responsible for the safe arrival of all her passengers. The train has no buffet car and with rumbling stomachs we discover, to our dismay, that at no other station where we spend hour after useless hour at a standstill, do any babushkas with baskets of rolls, cabbage or fish appear.

The stops become colder, the air thinner and somewhere, after hours of travelling east, the first passengers are drunk enough to start bothering us foreigners. Early in the morning and still half asleep, we take a taxi from Nevinnomyssk in South Russia to tiny Cherkessk, the sleepy capital of the North Caucasian republic of Karachay-Cherkessia. While in Sochi 50 billion dollars are being pumped into the Olympics, on the other side of the mountains time seems momentarily to stand still.

Bus station of Cherkessk, Karachay-Cherkessia, 2008.

The North Caucasus

Russia

, if you look from west to east. Adygea, through which we travelled by train at night, is the first, followed by Kabardino-Balkaria, then North Ossetia, Ingushetia, Chechnya and finally Dagestan on the Caspian Sea.